The Harmonisation of Mind and Breath :

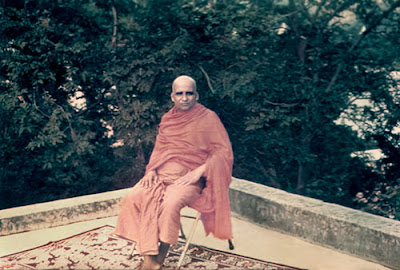

Swami Krishnananda

The Harmonisation of Mind and Breath :

----------------------------------------------------------

It will be observed that we hold our breath during any act of concentration in our daily lives. When we are walking along the edge of a precipice, we hold our breath. When we climb a tree, we hold our breath. Perhaps when walking on a tightrope, the circus performer also holds his breath. When we are about to do something which requires our total attention, or at least most of it, our breath is automatically held. It is not that we are deliberately doing pranayama here, but our breath is suspended of its own accord. This shows the mutual relationship between thought and the vital force. It is impossible for the mind to concentratedly pay attention to anything when the breath is heaving like a bellows. When we concentrate while listening to a lecture, we hold our breath. When we gaze at an object with awe-inspired wonder, we hold our breath.

All these are instances in life which demonstrate the relationship of prana with thought—and vice versa. All acts which need total attention of our whole personality draw up our energy together with the thought. Attention is another name for the concentration of our whole being. Wherever there is attention, the whole of us is there. In this form of mental attention, it is not merely the breath that is suspended, but all the sense organs as well. We cease to see, hear, smell, taste and touch at that time. When we are concentratedly looking at something or gazing at an object with attention, we will not hear sounds unless they are very loud. We may not even be able to see things moving near us or persons walking around us in this concentrated state. In this instance, the concentration of the mind, the cessation of the function of the breath, and the withdrawal of the senses all take place together.

Hence it is that in one single effort of yoga preparation, pranayama, pratyahara and dharana take place simultaneously. It is towards this end that the practice of pranayama is practised, as it is an essential limb in the concentration of the mind. One of the aphorisms of Patanjali says that the connection of the vital energy with the mind is such that the stoppage of the breath, even for a few minutes, would bring the mind to its normal condition. There are agitations of force which affect the mind, and these agitations are called “tendencies to pleasure and pain”. Intense exhilaration and intense grief are the two points between which the mind roves in its usual activities. In both these functions of the mind, the vital energy is carried along together with the mind.

If a bird is tied with a thread to a peg, and the thread’s connection with the peg is broken, the bird carries the thread wherever it moves because the thread is connected with the bird and not with the peg. Likewise is the mind’s relation with the prana. The oscillation of the mind is the same as the vacillation of the prana, and it is impossible for the one to function without the function of the other. Oftentimes a comparison is made between the relationship of the two and the relationship between the inner mechanism of a watch and its hands. The mechanism moves the hands, and the hands themselves have some sort of effect upon the mechanism working within so that when we hold the hands, the mechanism is suspended within for the time being. In the same way, if we stop the mechanism, the hands cease moving.

The Retention of Breath :

----------------------------------

A deep exhalation and retention is what Patanjali prescribes in one of his aphorisms to bring about a balance in the thinking process. Intense agitation of the mind caused by any external factor can be brought to a cessation, temporarily at least though not permanently, by deep expulsion and retention of the breath. If we do not want to think something, we can expel the breath and hold it, and the thought will cease to operate. The teacher assures us that if this process is repeated for a few minutes the mind will get accustomed to this cessation of function, and the agitation will cease. Any kind of extreme in thinking will be rectified by exerting a pressure on it through the operation of the prana in this practice of expulsion and retention. The retention can also be done after inhalation, and not merely after expulsion. The retention is called kumbhaka which means ‘holding or filling’ in Sanskrit. Kumbhaka also means ‘a pot’, and filling something as if filling a pot is kumbhaka. We fill ourselves with the force of vitality in the practice of kumbhaka. The filling is done either after deep inhalation or after deep exhalation—both these are important means of pranayama.

There are four types of kumbhaka described in the aphorisms of Patanjali. One is, as I mentioned, expulsion and retention. We breathe out, deeply and calmly, and hold the breath for a few seconds. Breathe in deeply and calmly again and hold the breath again for a few seconds. These are twin pranayamas—internal kumbhaka and external kumbhaka. The third type is the kumbhaka that is practised by alternative breathing, which means breathing in deeply through the left nostril, then holding the breath and then exhaling through the right. This coupled process of inhalation, retention and exhalation is supposed to be one round of pranayama. Easy, comfortable pranayama it is called—sukha-purvaka. This pranayama is easy to practise when it is done together with this alternate system of breathing. This is the third type of retention, along with the others that are coupled with expulsion and inhalation.

The fourth one is the most important of all, and it is this which is of consequence in the yoga practice. This is supposed to be the culmination of pranayama, and it is generally reached by some sort of training in the other three processes. The earliest stage would be expulsion and retention. Then the next stage would be inhalation and retention. The third would be alternate breathing and retention. Through a graduated practice of these one has to gain control over the breath. The fourth one, which is regarded as more important than all others, is called kevala kumbhaka, or automatic suspension of breath, and it is not attended with inhalation and exhalation. If we are suddenly taken unawares by something which we did not expect, we hold the breath without inhalation or exhalation. We do not know what is happening to the breath. It just stops, that is all. The mind is suspended in its function at once, because of the unexpected arrival of an event. Suddenly thought stops and breath stops. In concentration of any kind, the retention that follows is of this kind.

The raja and jnana yogins especially lay stress on this type of pranayama. As a matter of fact, they do not otherwise lay stress on pranayama at all, as this higher form follows automatically in the wake of concentration. The emphasis is more on concentration of mind than on the retention of breath as a lower process. When our interest in anything is immense, our concentration also is comparatively great. When we read a book with tremendous interest, our concentration on the subject is such that our breath will slow down automatically, and pranayama is automatically practised there. When we are to appear for an examination and there are only fifteen minutes till the bell rings and we are trying to remember some passage quickly, we will be earnestly turning through some pages. Our concentration on the theme would be such that we will not be listening to anything nor seeing anything at that time other than the crucial theme. Our minds are on the subject in such concentration that our breath also is there. When the breath and the mind go together hand in hand, neither function. The kevala kumbhaka, or the automatic suspension of the breath, is coupled with the act of concentration of mind, and it is difficult to say where one begins and the other ends. They are like two parallel lines moving side by side, starting together, moving with the same speed, and ending also at the same point. Kevala kumbhaka and the stoppage of the mind are parallel movements of a single force.

Here we may be reminded of the great controversy concerning the body-mind relationship. Materialists and behaviourists contend that the mind is controlled by reflexes of the body functions—going even to the extent of saying that the mind is only an excretion, as it were, of bodily energy. The idealists contend that the body is regulated and operated upon by the thought force, rather than the other way round. The debate has led to philosophical disputes with both arguing for two different points of view or angles of vision, one emphasising the mind and the other the body. Neither of them led to definite conclusions, because the fact seems to be that the one is not dependent on the other, as these schools seem to think.

It is not true that the body is entirely the master of the mind as the realists, materialists or the behaviourists think. Nor is it true to go to the other extreme of the idealists, in saying that the mind is entirely the master of the body, and the body would do whatever the mind says. There is no such total dependence of the one on the other. They seem to be moving in a parallel manner towards a destination common to both, like two legs walking, where we cannot say which determines the other. We cannot say that the right leg is the master of the left or the other way round. The two walk together symmetrically towards a purpose common to both. There seems to be a purpose transcending the movements of the legs, and it is this purpose that keeps the movements of the two legs in balance.

Likewise, there seems to be a higher purpose regulating the body and the mind. It would not be wisdom to think that one of them is the master of the other. The two are regulated by a single tendency, and this tendency is purposive and teleological, as the philosophers tell us. This realisation is important in our consideration of the practice in yoga. In all philosophical discussions people take either this side or that side, and it is difficult to encompass all sides at the same time. This is why philosophy has not helped mankind much, because the philosophies ended only as theories, schools of thought, doctrines or arguments. We have big books on philosophy, but finally we are told nothing conclusive although so many things have been said. To shift the arguments and to organically relate them to a systematic whole is a hard thing, because that requires a mind which can see through to the substance of the different arguments and into the good points and the necessary connecting links of the different sides of the discussion. This process, albeit difficult, has to be employed in our understanding of the relationship between mind and body.

This mind-body relationship has also led to debate between hatha yoga and the raja and jnana yoga schools. Just as in the West we have the difference between behaviourism and idealism in psychology, so too do we have the same debate between the hatha yogins and jnana yogins here in India. Hatha yoga emphasises prana and the bodily system more than the mind, whereas the raja yoga and more pointedly the jnana yoga emphasise the mind and the reason more than the body and the prana. The one says that the body and prana control the mind; the other says the mind and the reason control the prana and the body.

Prana and the Mind :

------------------------------

Neither of these need take much of our time, because these are viewpoints, and we know what a viewpoint means. It is only a picture of one side of a complete whole, and we should not look at anything from only one side. It is difficult to know the nature of any substance by referring to it by a few characteristics alone. In medical science and psychology it is seen that mental illness can affect the body, and bodily illness can affect the mind. We are supposed to be psychophysical organisms, not merely bodies or minds. We are an organic structure of body and mind taken together and not merely a mind thinking in the air without a body. Nor are we a body lumbering like a cart without a thought within. Hence, it is necessary to understand the proper relationship of prana and mind. In our study of yoga practice, attention should be given to the importance of prana as well as to the mind in their intrinsic relationship rather than their outer manifestation. It is the soul-force within us that acts as the relationship between the body and the mind. We have a soul, apart from the thinking process of the mind and the breathing activity of the prana.

This should not be missed in our study of yoga. Of course, to define the soul is such a difficult thing to do. Some peculiar something is this soul that we are, such that it expresses itself as thinking on one side and activity on the other side. This is the reason why when one side is touched, the other side also is automatically touched. To touch the right arm would be equal in effect to touching the left arm, because the communication will be conveyed through the system of the body. This is the reason why pranayama helps in concentration of mind, and why concentration of mind has an effect on the cessation of the breath. One acts on the other, and when we carefully consider the matter, we will realise both go together.

Any attempt at the harmonisation of the breathing process will not be a waste. There is no need to go to excesses on either side, as I have already mentioned. There are hatha yogins like the grammarians in Sanskrit, who go on studying grammar throughout their lives without actually learning the literature. Likewise, our lives may go only towards the practice of pranayama alone, and this would be a mistake which we should not commit, because pranayama and asana are not ends in themselves. They are supposed to help us in the practice of true yoga. May I once again mention that all the limbs of yoga are to act together in a concentrated focus, right from yama-niyama onwards, because yoga is the total effort of the whole system in which all the limbs of yoga get concentrated. Yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana—all get focused in one concentrated energy when we practise what is true yoga.

There is a difference between the rungs of a ladder and the limbs of yoga, thought many times we are told that the limbs of yoga are like rungs of a ladder. When we climb the second rung on the ladder, we do not continue to touch the first rung. The first rung is over, so that when we climb the higher rungs, the lower rungs are no longer touched by our feet. But this is not so in the case of the limbs of yoga. The rungs in the ladder are not organically connected, because they are mechanically fixed and thereby unrelated to one another. The limbs of yoga are not mechanically disconnected, but rather organically related. In an act of concentration or meditation, all the limbs of yoga take part at once. To give a humorous example, it is like monkeys attacking. When they attack, all attack together. They do not come one or two at a time—they come in a group.

Likewise, there is a deliberate mustering of all the forces which constitute the limbs of yoga. The whole soul practises yoga. In this attempt at the total concentration of the personality in yoga, it is difficult to say which limb is more important than the other and which is subsidiary to the other. The logical arrangement of asana, pranayama and pratyahara, in that order, is only for convenience in understanding and for ease in practice. It does not mean that they actually have to be arranged in that order.

The process of pranayama in yoga is a technique of the harmonisation of the vital energy through the simultaneous employment of the intermediary process of pratyahara, or the withdrawal of the senses, leading to a harmonisation of the thinking process. As I mentioned, in deep concentration the senses may stop functioning temporarily, and the breath also is held. When we enjoy a beautiful landscape when the sun is about to set, our whole attention is there, and we do not hear sounds or have sensory relationships to anything else. The breath also is temporarily held. Pranayama, pratyahara and dharana are the three terms used in Sanskrit, and mean respectively: the retention of the vital force, the cessation of the function of the sense organs in respect to their objects, and the concentration or attention of the mind. All these go together.

While a position in an asana can help in the concentration of the mind, there are occasions when interest is sufficiently intense that this concentration can take place in other poses also. Sometimes when we go for a walk, we will be deeply thinking something and we will not know that we have reached our destination. This must have happened to many of us. We just reach our destination—that is all we know. We do not know that we have been walking at all, because the concentration is so strongly focused on the theme that is occupying the mind. The concentration of the mind is not necessarily connected with a particular posture of the body, though we may choose a particular posture for practical convenience in the earlier stages.

As a matter of fact, in concentration of mind we forget the existence of the body itself, so that we do not know what posture it is occupying. It all depends upon the interest. Most important of all things is interest, which takes various forms such as love, affection, concentration, etc. Interest is paramount in yoga, just as interest is paramount in every field of activity in life. Where there is no interest in anything, there is no success. Interest depends, at least to some extent, on understanding. When we do not understand a thing, we cannot also have an interest in it. Through this laborious process of the analysis of the techniques of yoga, we have tried to bring our minds up to the point of grasping this important conclusion, namely, that the limbs of yoga, as well as the organs of the body and the mind—all of these in their totality—approach the total which is Reality.

It is not a part moving towards the whole. We do not know what is moving towards what. The whole rouses itself into the consciousness of the whole, which is symbolically stated in a famous mantra that is daily repeated: Purnamadah, purnamidam, purnat purnamudachyate—The whole is moving towards the whole, the whole has come out of the whole, and when the whole has been removed from the whole, the whole only remains. Such is this movement of the whole towards the whole in yoga, where the motion also is a whole, that which moves is a whole, that to which the whole moves also is a whole—everything is whole. No partial question arises here.

The practice of pranayama is also an organic process; therefore, it is not merely a mechanical act of the breath. The organic relationship of pranayama to pratyahara, which is the next step, is very interesting. Just as pranayama means the harmonisation of the vital energy by manipulation of the process of inhalation and exhalation, and which tends toward cessation, pratyahara means the very same act of the harmonisation of the sensory activities. It is not simply a withdrawal, as we have perhaps been told. It is an equilibration of the forces of the senses. All yoga is harmony—there is no withdrawal or expulsion. It is not projecting something or withdrawing something as much as it is a harmonising, which may appear to be a kind of withdrawal. Withdrawal of externality is harmony. In the so-called withdrawal in pratyahara or the abstraction of the sense powers, what happens really is the channelisation of mental energy through the senses is harmonized, and there is no further channelisation. The streams of the water reservoir are prevented from moving in different directions, and the waters fill the reservoir to its brim, filled to overflowing.

Our mind is like a reservoir of energy, and it has streams—five streams at least. The sense organs are streams of force. The prana is the propelling inclination of force which sends this energy to the channels of sense. The mind, the senses and the prana are thus connected. If the mind is the reservoir, and if the senses are the channels through which the water of the reservoir flows, the prana is the inclination that is needed for the water to flow through the channels. The prana therefore is the propelling energy. If there is no inclination, the water will not flow. The inclination towards an object of sense is the work of the prana, the channelisation is the senses and the force is the mind. The mind supplies the motive behind the activity—both of the prana and the senses.

It is difficult to find an equivalent in the English language for what is meant by the ‘psychological organ’. It is something which has in it the seed of the forces of activity—not only of the mind but also of the senses and the prana. This psychological organ is something which is unitary in us that works as mind, senses and prana. On the one side it is the activity of the force of vitality; on another side it is the senses trying to cognise and perceive things, and on another side it is the thinking process. Very few students of yoga would find it easy to practise this pratyahara of the whole psychological organ. They may hold their breath through force of will and by holding the nose, but they cannot hold the senses so easily. The senses are turbulent and impetuous in their movement. They find their way out, whatever be our effort in controlling them.

Subjugation of the Senses :

-------------------------------------

More difficult than asana is pranayama, and more difficult than pranayama is pratyahara. We will find that the higher rungs are more difficult to attain than the lower ones, so that we may be perfect in asana but not in pranayama. We may be a little adept in pranayama, but not in pratyahara and dharana, because the higher things that we have to reach in yoga are more and more invisible and out of physical control. They become ethereal and more pervasive in their activity. That which is more pervasive is also more difficult to subjugate. The senses are difficult to understand. We do not know what a sense organ means, so how can we control a sense organ? Why should we control the sense organs—and even if we try, what are the means that we are to employ? Doubts of this kind may also occur to the minds of students of yoga. “What on earth am I going to achieve by this withdrawal, and into what am I going to withdraw?”

'Withdrawal' means withdrawal of something, by something, into something. What is this ‘thing’ into which we are going to withdraw? Where does it finally land us after all? This difficulty which is of the nature of a doubt will also create a lack of interest. We know what will happen to us if we have no interest—nothing will be achieved. Therefore, in the stages of yoga from pratyahara onwards, the understanding should exercise itself in a more predominant manner than in the earlier stages. While some sort of success can be achieved up to the stage of pranayama, there are very few who can achieve success later on. We can maybe hold our breath, but we cannot control the senses, because the reason is diversely directed.

We are brought up in such a way in human society, right from our childhood, that we have been taught to think in terms only of the senses. To now revise the way of thinking and sensory activity is a herculean task. It requires a new education altogether, which we are trying to have nowadays when we seem to be too old to learn anything new. The old impressions of our early upbringing, from childhood onwards, have an impact on our present way of thinking, and again and again the old mind starts saying: “What are you doing to me?” The new child is unable to answer these questions of the old mind within. “Just keep quiet; don’t pursue this,” says the old mind. Many times we listen to this old whisper, because it is rare that we can completely hush this inner voice of the habituated mind which has been our way of thinking since childhood.

After all, what would be the effort that we will have to put forth in the practice of yoga, and for how many years? We may practise for a few months or maybe even two or three years, but it is nothing compared to the number of years that we have lived in this world. We have been living in this world for so many years—right from childhood—and we have been thinking wrongly during all that time. We have been believing that this way of thinking is the right thing, and now after one or two years or maybe just a few months, we have been trying to think rightly. But the whole habit will not go away so easily, because the emotions are especially turbulent. They will not listen to us at all, and it is the emotions that regulate the workings of the senses.

This is very important to remember. Our logical arguments are not going to help us in any manner, because the senses are not going to listen to them. Logic may appear to have some effect on the senses, but logic is ultimately of no help if it is not connected with the inner feeling. There is a story related to this. One of the young Muslim rulers who lived in India had a very good spiritual teacher, and the teacher taught him wonderful things of the heavens, the philosophy of creation, and many mysterious things of the world. As he had learned everything, the young ruler was declared to be a master of philosophy—very learned in the sacred lore of Islam and the general philosophy of those times. The young lad listened to everything and studied the whole of philosophy, but yet he had not fully understood things with his whole heart. The master returned to his own home, and the student wrote a plaintive letter to him. “My revered Master, I am grateful for all that you have taught me. You have taught me many things, but you have not taught me one single useful thing! For instance, I do not know how to attack an enemy’s fort, how to occupy my throne for the longest period possible, how to outwit my opponents, how to regain what I have lost in this material world, or how politically to manoeuvre armies. You haven’t taught me any of these things.” This reliance on logic rather than wisdom was the way of thinking with which the lad was brought up, and the mysteries of the cosmos did not seem to help him at all. He had heard all these great truths, but his previous erroneous way of thinking kept him from fully understanding them, because he was stuck in his old way of thinking.

The Heart and Not Just the Logic :

-------------------------------------------

This is exactly the way in which the mind will receive teachings when they are presented in a logical form. There is a beautiful saying of Pascal: “The heart has a reason which reason does not know.” The heart has a logic of its own, and the inductive and deductive processes of the schools of logic are alien to the logic of the heart. Whenever we listen to any logic, we say, “Yes, yes, but...” This “but” will not leave us at any time. The “yes, yes” response is the logic of the head, while the “but” is our heart speaking. There will always be a “but” for every thinking that we do in this world. It is this “but” that prevents us from successfully practising pratyahara. Just observe—we have an objection for everything. We never listen to anything wholly, nor can we agree with it completely. When I say “we” here, I mean by that our emotions. The heart speaks a language of its own, and the language of the heart is the most powerful of expressions. The intellect will be a failure in this attempt, if the logic has not touched the heart. The logic has not done its work if conviction has not become feeling. Intellectual conviction will not help us in yoga. It is this difference between the activities of the heart and the head that has been the cause of the failure of many students in their practice. We feel something and start thinking another thing altogether. That which we feel is our life, and that which we think is only an outward expression of our personality.

The pratyahara process therefore is not only an external expression of our personality, and it is not only an intellectual or a physical function. It is a function of emotion which is the driving force in our personalities. That which drives us to do anything in this world is emotion. Where emotion is absent, then everything cools down. Emotion supplies us with the necessary warmth of life. Where emotion is absent, either this way or that way, life is cold, insipid and without any significance. When we speak from our emotions, we speak with force. When we run, we run with force. This we do whether we like a thing or dislike a thing. We express our vehemence with force, and we also express our wonderment with force. “How wonderful!” or “How stupid!” Both we will say with force. This force comes from the emotions. Where emotion is absent, we have no force, and we become a cold, dead object.

Hence, emotion is not a bad thing, because it supplies the power. However, we also know what power means—it can be used for a proper and good purpose or for a destructive purpose. As emotion is an amoral something which is necessary in us, and it can be diverted either to this side or that side—like a double-edged sword or like fire. Can we say fire is wholly good or bad? No one can answer this question. We cannot say fire is good or bad. It is good if it is used for cooking our meals or warming ourselves in winter, but it is bad if it is used to set fire to somebody’s house or to devastate cities.

Force is neither good nor bad. It is an amoral energy of the universe. Emotion is the manifestation of force in our personality, and this force usually works as sensory activity through the function of the prana, as we have seen. This is both the difficulty as well as the necessity in the regulation of the activities of sense. For this purpose we have to analyse the structure of our interests and our emotional relationships, rather than try to philosophically analyse the structure of creation or the concepts of logic in philosophy. In pratyahara, the subject of analysis and understanding is our emotional relationship with things and the hidden impulses towards satisfaction of any kind. The necessity for pratyahara arises on account of our feelings for satisfaction in things other than in the objectives of yoga. As our satisfaction is diverted to things other than the objectives that we seek in yoga, the need for pratyahara arises.

We know very well that we can wean ourselves from anything—but not from an object of satisfaction. There is nothing in this world which can attract us so much as that which satisfies us. There is nothing which we want except that which satisfies us, and if the objects of sense can satisfy us, nothing can be more difficult for us than to wean the mind from this satisfaction. Hence it is that in pratyahara we are always at a dead end, and we cannot move further. Most students of yoga are stuck here, and they cannot go further. When people have unintelligently tried to control the senses through pratyahara, the attempts have not ended in success. They ended in tensions and complexes of various kinds and also in difficulties which later began to harass them in many ways—all because emotion was regarded as an unimportant factor in human life. The mechanical process of the subjugation of the senses was employed as they tried to sit with force in a particular asana or tried to hold the breath with force. We may employ some force in things, but we cannot employ force in the control of the senses, and it is un-wisdom to try it.

Through the stage of pratyahara, we come to the threshold of the mind. That is why the difficulty is greater here than with asana or pranayama. While in the earlier two stages of asana and pranayama we were a little removed from the mind and mental processes, we are now coming to the borderland of thinking itself, and we are touching the vital points of the mind when controlling the senses. We will realise to our surprise that pratyahara is a very interesting subject of study, and it involves many minor processes of analysis of mind in its emotional aspects. When we touch pratyahara, we have touched our own weak spots. That is why we would not like to touch it, either in ourselves or in others, if possible. We know what a weak spot is—a spot which we would not like to touch. Now we are about to touch it, and when this happens we are completely in dismay, and we do not know what to do with ourselves. But it has to be done one day or the other, and hence it is that in pratyahara, we may take a little more time to understand and tackle the situation.

But once a step is taken, it has to be taken firmly. There is no use hurrying forward in trying to control the senses. “Today I’ll control the eyes, and tomorrow I’ll control the ears.” We cannot do that and think that five days later the senses will all be controlled. This cannot be achieved, because all the five senses work together. There is no such thing as controlling only one sense. The five senses are like five holes in a vessel through which the contents will leak out. If we plug one hole, the force through which the expression will manifest itself elsewhere will be very vehement. We should not try to plug these holes one after the other. We have to deal simultaneously with them, and for this a very sound technique has to be employed—which should be our next subject of study.

Swami Krishnananda.

The Harmonisation of Mind and Breath :

----------------------------------------------------------

It will be observed that we hold our breath during any act of concentration in our daily lives. When we are walking along the edge of a precipice, we hold our breath. When we climb a tree, we hold our breath. Perhaps when walking on a tightrope, the circus performer also holds his breath. When we are about to do something which requires our total attention, or at least most of it, our breath is automatically held. It is not that we are deliberately doing pranayama here, but our breath is suspended of its own accord. This shows the mutual relationship between thought and the vital force. It is impossible for the mind to concentratedly pay attention to anything when the breath is heaving like a bellows. When we concentrate while listening to a lecture, we hold our breath. When we gaze at an object with awe-inspired wonder, we hold our breath.

All these are instances in life which demonstrate the relationship of prana with thought—and vice versa. All acts which need total attention of our whole personality draw up our energy together with the thought. Attention is another name for the concentration of our whole being. Wherever there is attention, the whole of us is there. In this form of mental attention, it is not merely the breath that is suspended, but all the sense organs as well. We cease to see, hear, smell, taste and touch at that time. When we are concentratedly looking at something or gazing at an object with attention, we will not hear sounds unless they are very loud. We may not even be able to see things moving near us or persons walking around us in this concentrated state. In this instance, the concentration of the mind, the cessation of the function of the breath, and the withdrawal of the senses all take place together.

Hence it is that in one single effort of yoga preparation, pranayama, pratyahara and dharana take place simultaneously. It is towards this end that the practice of pranayama is practised, as it is an essential limb in the concentration of the mind. One of the aphorisms of Patanjali says that the connection of the vital energy with the mind is such that the stoppage of the breath, even for a few minutes, would bring the mind to its normal condition. There are agitations of force which affect the mind, and these agitations are called “tendencies to pleasure and pain”. Intense exhilaration and intense grief are the two points between which the mind roves in its usual activities. In both these functions of the mind, the vital energy is carried along together with the mind.

If a bird is tied with a thread to a peg, and the thread’s connection with the peg is broken, the bird carries the thread wherever it moves because the thread is connected with the bird and not with the peg. Likewise is the mind’s relation with the prana. The oscillation of the mind is the same as the vacillation of the prana, and it is impossible for the one to function without the function of the other. Oftentimes a comparison is made between the relationship of the two and the relationship between the inner mechanism of a watch and its hands. The mechanism moves the hands, and the hands themselves have some sort of effect upon the mechanism working within so that when we hold the hands, the mechanism is suspended within for the time being. In the same way, if we stop the mechanism, the hands cease moving.

The Retention of Breath :

----------------------------------

A deep exhalation and retention is what Patanjali prescribes in one of his aphorisms to bring about a balance in the thinking process. Intense agitation of the mind caused by any external factor can be brought to a cessation, temporarily at least though not permanently, by deep expulsion and retention of the breath. If we do not want to think something, we can expel the breath and hold it, and the thought will cease to operate. The teacher assures us that if this process is repeated for a few minutes the mind will get accustomed to this cessation of function, and the agitation will cease. Any kind of extreme in thinking will be rectified by exerting a pressure on it through the operation of the prana in this practice of expulsion and retention. The retention can also be done after inhalation, and not merely after expulsion. The retention is called kumbhaka which means ‘holding or filling’ in Sanskrit. Kumbhaka also means ‘a pot’, and filling something as if filling a pot is kumbhaka. We fill ourselves with the force of vitality in the practice of kumbhaka. The filling is done either after deep inhalation or after deep exhalation—both these are important means of pranayama.

There are four types of kumbhaka described in the aphorisms of Patanjali. One is, as I mentioned, expulsion and retention. We breathe out, deeply and calmly, and hold the breath for a few seconds. Breathe in deeply and calmly again and hold the breath again for a few seconds. These are twin pranayamas—internal kumbhaka and external kumbhaka. The third type is the kumbhaka that is practised by alternative breathing, which means breathing in deeply through the left nostril, then holding the breath and then exhaling through the right. This coupled process of inhalation, retention and exhalation is supposed to be one round of pranayama. Easy, comfortable pranayama it is called—sukha-purvaka. This pranayama is easy to practise when it is done together with this alternate system of breathing. This is the third type of retention, along with the others that are coupled with expulsion and inhalation.

The fourth one is the most important of all, and it is this which is of consequence in the yoga practice. This is supposed to be the culmination of pranayama, and it is generally reached by some sort of training in the other three processes. The earliest stage would be expulsion and retention. Then the next stage would be inhalation and retention. The third would be alternate breathing and retention. Through a graduated practice of these one has to gain control over the breath. The fourth one, which is regarded as more important than all others, is called kevala kumbhaka, or automatic suspension of breath, and it is not attended with inhalation and exhalation. If we are suddenly taken unawares by something which we did not expect, we hold the breath without inhalation or exhalation. We do not know what is happening to the breath. It just stops, that is all. The mind is suspended in its function at once, because of the unexpected arrival of an event. Suddenly thought stops and breath stops. In concentration of any kind, the retention that follows is of this kind.

The raja and jnana yogins especially lay stress on this type of pranayama. As a matter of fact, they do not otherwise lay stress on pranayama at all, as this higher form follows automatically in the wake of concentration. The emphasis is more on concentration of mind than on the retention of breath as a lower process. When our interest in anything is immense, our concentration also is comparatively great. When we read a book with tremendous interest, our concentration on the subject is such that our breath will slow down automatically, and pranayama is automatically practised there. When we are to appear for an examination and there are only fifteen minutes till the bell rings and we are trying to remember some passage quickly, we will be earnestly turning through some pages. Our concentration on the theme would be such that we will not be listening to anything nor seeing anything at that time other than the crucial theme. Our minds are on the subject in such concentration that our breath also is there. When the breath and the mind go together hand in hand, neither function. The kevala kumbhaka, or the automatic suspension of the breath, is coupled with the act of concentration of mind, and it is difficult to say where one begins and the other ends. They are like two parallel lines moving side by side, starting together, moving with the same speed, and ending also at the same point. Kevala kumbhaka and the stoppage of the mind are parallel movements of a single force.

Here we may be reminded of the great controversy concerning the body-mind relationship. Materialists and behaviourists contend that the mind is controlled by reflexes of the body functions—going even to the extent of saying that the mind is only an excretion, as it were, of bodily energy. The idealists contend that the body is regulated and operated upon by the thought force, rather than the other way round. The debate has led to philosophical disputes with both arguing for two different points of view or angles of vision, one emphasising the mind and the other the body. Neither of them led to definite conclusions, because the fact seems to be that the one is not dependent on the other, as these schools seem to think.

It is not true that the body is entirely the master of the mind as the realists, materialists or the behaviourists think. Nor is it true to go to the other extreme of the idealists, in saying that the mind is entirely the master of the body, and the body would do whatever the mind says. There is no such total dependence of the one on the other. They seem to be moving in a parallel manner towards a destination common to both, like two legs walking, where we cannot say which determines the other. We cannot say that the right leg is the master of the left or the other way round. The two walk together symmetrically towards a purpose common to both. There seems to be a purpose transcending the movements of the legs, and it is this purpose that keeps the movements of the two legs in balance.

Likewise, there seems to be a higher purpose regulating the body and the mind. It would not be wisdom to think that one of them is the master of the other. The two are regulated by a single tendency, and this tendency is purposive and teleological, as the philosophers tell us. This realisation is important in our consideration of the practice in yoga. In all philosophical discussions people take either this side or that side, and it is difficult to encompass all sides at the same time. This is why philosophy has not helped mankind much, because the philosophies ended only as theories, schools of thought, doctrines or arguments. We have big books on philosophy, but finally we are told nothing conclusive although so many things have been said. To shift the arguments and to organically relate them to a systematic whole is a hard thing, because that requires a mind which can see through to the substance of the different arguments and into the good points and the necessary connecting links of the different sides of the discussion. This process, albeit difficult, has to be employed in our understanding of the relationship between mind and body.

This mind-body relationship has also led to debate between hatha yoga and the raja and jnana yoga schools. Just as in the West we have the difference between behaviourism and idealism in psychology, so too do we have the same debate between the hatha yogins and jnana yogins here in India. Hatha yoga emphasises prana and the bodily system more than the mind, whereas the raja yoga and more pointedly the jnana yoga emphasise the mind and the reason more than the body and the prana. The one says that the body and prana control the mind; the other says the mind and the reason control the prana and the body.

Prana and the Mind :

------------------------------

Neither of these need take much of our time, because these are viewpoints, and we know what a viewpoint means. It is only a picture of one side of a complete whole, and we should not look at anything from only one side. It is difficult to know the nature of any substance by referring to it by a few characteristics alone. In medical science and psychology it is seen that mental illness can affect the body, and bodily illness can affect the mind. We are supposed to be psychophysical organisms, not merely bodies or minds. We are an organic structure of body and mind taken together and not merely a mind thinking in the air without a body. Nor are we a body lumbering like a cart without a thought within. Hence, it is necessary to understand the proper relationship of prana and mind. In our study of yoga practice, attention should be given to the importance of prana as well as to the mind in their intrinsic relationship rather than their outer manifestation. It is the soul-force within us that acts as the relationship between the body and the mind. We have a soul, apart from the thinking process of the mind and the breathing activity of the prana.

This should not be missed in our study of yoga. Of course, to define the soul is such a difficult thing to do. Some peculiar something is this soul that we are, such that it expresses itself as thinking on one side and activity on the other side. This is the reason why when one side is touched, the other side also is automatically touched. To touch the right arm would be equal in effect to touching the left arm, because the communication will be conveyed through the system of the body. This is the reason why pranayama helps in concentration of mind, and why concentration of mind has an effect on the cessation of the breath. One acts on the other, and when we carefully consider the matter, we will realise both go together.

Any attempt at the harmonisation of the breathing process will not be a waste. There is no need to go to excesses on either side, as I have already mentioned. There are hatha yogins like the grammarians in Sanskrit, who go on studying grammar throughout their lives without actually learning the literature. Likewise, our lives may go only towards the practice of pranayama alone, and this would be a mistake which we should not commit, because pranayama and asana are not ends in themselves. They are supposed to help us in the practice of true yoga. May I once again mention that all the limbs of yoga are to act together in a concentrated focus, right from yama-niyama onwards, because yoga is the total effort of the whole system in which all the limbs of yoga get concentrated. Yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana—all get focused in one concentrated energy when we practise what is true yoga.

There is a difference between the rungs of a ladder and the limbs of yoga, thought many times we are told that the limbs of yoga are like rungs of a ladder. When we climb the second rung on the ladder, we do not continue to touch the first rung. The first rung is over, so that when we climb the higher rungs, the lower rungs are no longer touched by our feet. But this is not so in the case of the limbs of yoga. The rungs in the ladder are not organically connected, because they are mechanically fixed and thereby unrelated to one another. The limbs of yoga are not mechanically disconnected, but rather organically related. In an act of concentration or meditation, all the limbs of yoga take part at once. To give a humorous example, it is like monkeys attacking. When they attack, all attack together. They do not come one or two at a time—they come in a group.

Likewise, there is a deliberate mustering of all the forces which constitute the limbs of yoga. The whole soul practises yoga. In this attempt at the total concentration of the personality in yoga, it is difficult to say which limb is more important than the other and which is subsidiary to the other. The logical arrangement of asana, pranayama and pratyahara, in that order, is only for convenience in understanding and for ease in practice. It does not mean that they actually have to be arranged in that order.

The process of pranayama in yoga is a technique of the harmonisation of the vital energy through the simultaneous employment of the intermediary process of pratyahara, or the withdrawal of the senses, leading to a harmonisation of the thinking process. As I mentioned, in deep concentration the senses may stop functioning temporarily, and the breath also is held. When we enjoy a beautiful landscape when the sun is about to set, our whole attention is there, and we do not hear sounds or have sensory relationships to anything else. The breath also is temporarily held. Pranayama, pratyahara and dharana are the three terms used in Sanskrit, and mean respectively: the retention of the vital force, the cessation of the function of the sense organs in respect to their objects, and the concentration or attention of the mind. All these go together.

While a position in an asana can help in the concentration of the mind, there are occasions when interest is sufficiently intense that this concentration can take place in other poses also. Sometimes when we go for a walk, we will be deeply thinking something and we will not know that we have reached our destination. This must have happened to many of us. We just reach our destination—that is all we know. We do not know that we have been walking at all, because the concentration is so strongly focused on the theme that is occupying the mind. The concentration of the mind is not necessarily connected with a particular posture of the body, though we may choose a particular posture for practical convenience in the earlier stages.

As a matter of fact, in concentration of mind we forget the existence of the body itself, so that we do not know what posture it is occupying. It all depends upon the interest. Most important of all things is interest, which takes various forms such as love, affection, concentration, etc. Interest is paramount in yoga, just as interest is paramount in every field of activity in life. Where there is no interest in anything, there is no success. Interest depends, at least to some extent, on understanding. When we do not understand a thing, we cannot also have an interest in it. Through this laborious process of the analysis of the techniques of yoga, we have tried to bring our minds up to the point of grasping this important conclusion, namely, that the limbs of yoga, as well as the organs of the body and the mind—all of these in their totality—approach the total which is Reality.

It is not a part moving towards the whole. We do not know what is moving towards what. The whole rouses itself into the consciousness of the whole, which is symbolically stated in a famous mantra that is daily repeated: Purnamadah, purnamidam, purnat purnamudachyate—The whole is moving towards the whole, the whole has come out of the whole, and when the whole has been removed from the whole, the whole only remains. Such is this movement of the whole towards the whole in yoga, where the motion also is a whole, that which moves is a whole, that to which the whole moves also is a whole—everything is whole. No partial question arises here.

The practice of pranayama is also an organic process; therefore, it is not merely a mechanical act of the breath. The organic relationship of pranayama to pratyahara, which is the next step, is very interesting. Just as pranayama means the harmonisation of the vital energy by manipulation of the process of inhalation and exhalation, and which tends toward cessation, pratyahara means the very same act of the harmonisation of the sensory activities. It is not simply a withdrawal, as we have perhaps been told. It is an equilibration of the forces of the senses. All yoga is harmony—there is no withdrawal or expulsion. It is not projecting something or withdrawing something as much as it is a harmonising, which may appear to be a kind of withdrawal. Withdrawal of externality is harmony. In the so-called withdrawal in pratyahara or the abstraction of the sense powers, what happens really is the channelisation of mental energy through the senses is harmonized, and there is no further channelisation. The streams of the water reservoir are prevented from moving in different directions, and the waters fill the reservoir to its brim, filled to overflowing.

Our mind is like a reservoir of energy, and it has streams—five streams at least. The sense organs are streams of force. The prana is the propelling inclination of force which sends this energy to the channels of sense. The mind, the senses and the prana are thus connected. If the mind is the reservoir, and if the senses are the channels through which the water of the reservoir flows, the prana is the inclination that is needed for the water to flow through the channels. The prana therefore is the propelling energy. If there is no inclination, the water will not flow. The inclination towards an object of sense is the work of the prana, the channelisation is the senses and the force is the mind. The mind supplies the motive behind the activity—both of the prana and the senses.

It is difficult to find an equivalent in the English language for what is meant by the ‘psychological organ’. It is something which has in it the seed of the forces of activity—not only of the mind but also of the senses and the prana. This psychological organ is something which is unitary in us that works as mind, senses and prana. On the one side it is the activity of the force of vitality; on another side it is the senses trying to cognise and perceive things, and on another side it is the thinking process. Very few students of yoga would find it easy to practise this pratyahara of the whole psychological organ. They may hold their breath through force of will and by holding the nose, but they cannot hold the senses so easily. The senses are turbulent and impetuous in their movement. They find their way out, whatever be our effort in controlling them.

Subjugation of the Senses :

-------------------------------------

More difficult than asana is pranayama, and more difficult than pranayama is pratyahara. We will find that the higher rungs are more difficult to attain than the lower ones, so that we may be perfect in asana but not in pranayama. We may be a little adept in pranayama, but not in pratyahara and dharana, because the higher things that we have to reach in yoga are more and more invisible and out of physical control. They become ethereal and more pervasive in their activity. That which is more pervasive is also more difficult to subjugate. The senses are difficult to understand. We do not know what a sense organ means, so how can we control a sense organ? Why should we control the sense organs—and even if we try, what are the means that we are to employ? Doubts of this kind may also occur to the minds of students of yoga. “What on earth am I going to achieve by this withdrawal, and into what am I going to withdraw?”

'Withdrawal' means withdrawal of something, by something, into something. What is this ‘thing’ into which we are going to withdraw? Where does it finally land us after all? This difficulty which is of the nature of a doubt will also create a lack of interest. We know what will happen to us if we have no interest—nothing will be achieved. Therefore, in the stages of yoga from pratyahara onwards, the understanding should exercise itself in a more predominant manner than in the earlier stages. While some sort of success can be achieved up to the stage of pranayama, there are very few who can achieve success later on. We can maybe hold our breath, but we cannot control the senses, because the reason is diversely directed.

We are brought up in such a way in human society, right from our childhood, that we have been taught to think in terms only of the senses. To now revise the way of thinking and sensory activity is a herculean task. It requires a new education altogether, which we are trying to have nowadays when we seem to be too old to learn anything new. The old impressions of our early upbringing, from childhood onwards, have an impact on our present way of thinking, and again and again the old mind starts saying: “What are you doing to me?” The new child is unable to answer these questions of the old mind within. “Just keep quiet; don’t pursue this,” says the old mind. Many times we listen to this old whisper, because it is rare that we can completely hush this inner voice of the habituated mind which has been our way of thinking since childhood.

After all, what would be the effort that we will have to put forth in the practice of yoga, and for how many years? We may practise for a few months or maybe even two or three years, but it is nothing compared to the number of years that we have lived in this world. We have been living in this world for so many years—right from childhood—and we have been thinking wrongly during all that time. We have been believing that this way of thinking is the right thing, and now after one or two years or maybe just a few months, we have been trying to think rightly. But the whole habit will not go away so easily, because the emotions are especially turbulent. They will not listen to us at all, and it is the emotions that regulate the workings of the senses.

This is very important to remember. Our logical arguments are not going to help us in any manner, because the senses are not going to listen to them. Logic may appear to have some effect on the senses, but logic is ultimately of no help if it is not connected with the inner feeling. There is a story related to this. One of the young Muslim rulers who lived in India had a very good spiritual teacher, and the teacher taught him wonderful things of the heavens, the philosophy of creation, and many mysterious things of the world. As he had learned everything, the young ruler was declared to be a master of philosophy—very learned in the sacred lore of Islam and the general philosophy of those times. The young lad listened to everything and studied the whole of philosophy, but yet he had not fully understood things with his whole heart. The master returned to his own home, and the student wrote a plaintive letter to him. “My revered Master, I am grateful for all that you have taught me. You have taught me many things, but you have not taught me one single useful thing! For instance, I do not know how to attack an enemy’s fort, how to occupy my throne for the longest period possible, how to outwit my opponents, how to regain what I have lost in this material world, or how politically to manoeuvre armies. You haven’t taught me any of these things.” This reliance on logic rather than wisdom was the way of thinking with which the lad was brought up, and the mysteries of the cosmos did not seem to help him at all. He had heard all these great truths, but his previous erroneous way of thinking kept him from fully understanding them, because he was stuck in his old way of thinking.

The Heart and Not Just the Logic :

-------------------------------------------

This is exactly the way in which the mind will receive teachings when they are presented in a logical form. There is a beautiful saying of Pascal: “The heart has a reason which reason does not know.” The heart has a logic of its own, and the inductive and deductive processes of the schools of logic are alien to the logic of the heart. Whenever we listen to any logic, we say, “Yes, yes, but...” This “but” will not leave us at any time. The “yes, yes” response is the logic of the head, while the “but” is our heart speaking. There will always be a “but” for every thinking that we do in this world. It is this “but” that prevents us from successfully practising pratyahara. Just observe—we have an objection for everything. We never listen to anything wholly, nor can we agree with it completely. When I say “we” here, I mean by that our emotions. The heart speaks a language of its own, and the language of the heart is the most powerful of expressions. The intellect will be a failure in this attempt, if the logic has not touched the heart. The logic has not done its work if conviction has not become feeling. Intellectual conviction will not help us in yoga. It is this difference between the activities of the heart and the head that has been the cause of the failure of many students in their practice. We feel something and start thinking another thing altogether. That which we feel is our life, and that which we think is only an outward expression of our personality.

The pratyahara process therefore is not only an external expression of our personality, and it is not only an intellectual or a physical function. It is a function of emotion which is the driving force in our personalities. That which drives us to do anything in this world is emotion. Where emotion is absent, then everything cools down. Emotion supplies us with the necessary warmth of life. Where emotion is absent, either this way or that way, life is cold, insipid and without any significance. When we speak from our emotions, we speak with force. When we run, we run with force. This we do whether we like a thing or dislike a thing. We express our vehemence with force, and we also express our wonderment with force. “How wonderful!” or “How stupid!” Both we will say with force. This force comes from the emotions. Where emotion is absent, we have no force, and we become a cold, dead object.

Hence, emotion is not a bad thing, because it supplies the power. However, we also know what power means—it can be used for a proper and good purpose or for a destructive purpose. As emotion is an amoral something which is necessary in us, and it can be diverted either to this side or that side—like a double-edged sword or like fire. Can we say fire is wholly good or bad? No one can answer this question. We cannot say fire is good or bad. It is good if it is used for cooking our meals or warming ourselves in winter, but it is bad if it is used to set fire to somebody’s house or to devastate cities.

Force is neither good nor bad. It is an amoral energy of the universe. Emotion is the manifestation of force in our personality, and this force usually works as sensory activity through the function of the prana, as we have seen. This is both the difficulty as well as the necessity in the regulation of the activities of sense. For this purpose we have to analyse the structure of our interests and our emotional relationships, rather than try to philosophically analyse the structure of creation or the concepts of logic in philosophy. In pratyahara, the subject of analysis and understanding is our emotional relationship with things and the hidden impulses towards satisfaction of any kind. The necessity for pratyahara arises on account of our feelings for satisfaction in things other than in the objectives of yoga. As our satisfaction is diverted to things other than the objectives that we seek in yoga, the need for pratyahara arises.

We know very well that we can wean ourselves from anything—but not from an object of satisfaction. There is nothing in this world which can attract us so much as that which satisfies us. There is nothing which we want except that which satisfies us, and if the objects of sense can satisfy us, nothing can be more difficult for us than to wean the mind from this satisfaction. Hence it is that in pratyahara we are always at a dead end, and we cannot move further. Most students of yoga are stuck here, and they cannot go further. When people have unintelligently tried to control the senses through pratyahara, the attempts have not ended in success. They ended in tensions and complexes of various kinds and also in difficulties which later began to harass them in many ways—all because emotion was regarded as an unimportant factor in human life. The mechanical process of the subjugation of the senses was employed as they tried to sit with force in a particular asana or tried to hold the breath with force. We may employ some force in things, but we cannot employ force in the control of the senses, and it is un-wisdom to try it.

Through the stage of pratyahara, we come to the threshold of the mind. That is why the difficulty is greater here than with asana or pranayama. While in the earlier two stages of asana and pranayama we were a little removed from the mind and mental processes, we are now coming to the borderland of thinking itself, and we are touching the vital points of the mind when controlling the senses. We will realise to our surprise that pratyahara is a very interesting subject of study, and it involves many minor processes of analysis of mind in its emotional aspects. When we touch pratyahara, we have touched our own weak spots. That is why we would not like to touch it, either in ourselves or in others, if possible. We know what a weak spot is—a spot which we would not like to touch. Now we are about to touch it, and when this happens we are completely in dismay, and we do not know what to do with ourselves. But it has to be done one day or the other, and hence it is that in pratyahara, we may take a little more time to understand and tackle the situation.

But once a step is taken, it has to be taken firmly. There is no use hurrying forward in trying to control the senses. “Today I’ll control the eyes, and tomorrow I’ll control the ears.” We cannot do that and think that five days later the senses will all be controlled. This cannot be achieved, because all the five senses work together. There is no such thing as controlling only one sense. The five senses are like five holes in a vessel through which the contents will leak out. If we plug one hole, the force through which the expression will manifest itself elsewhere will be very vehement. We should not try to plug these holes one after the other. We have to deal simultaneously with them, and for this a very sound technique has to be employed—which should be our next subject of study.

Swami Krishnananda.

Comments